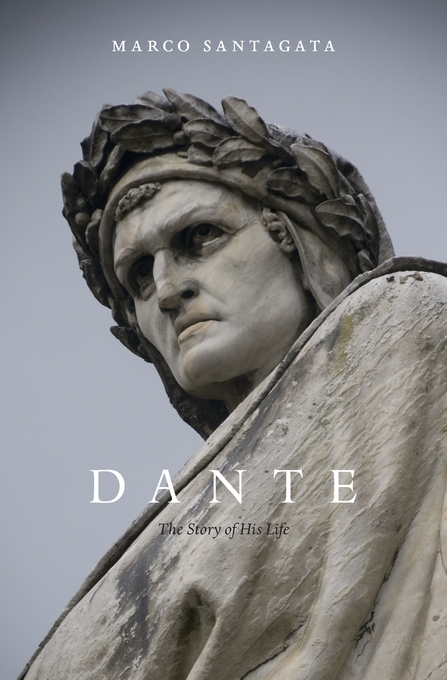

Dante – The Story of His Life

By Marco Santagata

Belknap/Harvard University Press – £25.00

Se tu segui tua stella

non puoi fallire a glorioso porto

If you follow your star,

you cannot fail to reach a glorious port

-Inf. xv 55-56

In the tenth and final chapter (‘Courtier (1316-1321)’) of a book simply strewn with overtly fraught Florentine discontentment, author Marco Santagata, hits home with such profound and informative effervescence, it’s enough to send any morally inclined reader running for the nearest hills of sanctified exacerbation: ”The allegorical interpretation, in effect, softened the prophetic and doctrinal aspects, which the Church authorities regarded as dangerous (in 1355 the provincial chapter of the Dominicans in Florence forbade monks to read Dante’s vernacular works).”

As such, by the time one has reached the nigh conclusion of Dante – The Story of His Life, one is, if nothing else, somewhat indebted to the supreme poet’s patient, and most perplexing of partisan philosophy.

Just one reason is accounted for by the mere fact that throughout Dante’s childhood and indeed, much of his adult life, his entire world was colorata in rosso/stained red (Inf.X 86) – due to the absurd and seemingly pointless inter-familial feuds of Ghibelline fugitives and Guelf reactionaries.

To be sure, reading the 302 pages of this book (excluding Appendix: Genealogical Tables, Abbreviations in Notes, Notes, Acknowledgements and Index) does unsurprisingly endear one into fully realising/comprehending: just how very little society has itself learnt from that of the ‘other.’

Niente.

In other words, anything which may appear slightly different or alien to that of our own social subscription and moral parameters, appears to have always been construed as reason enough to attack, victimise and ultimately desecrate. Santagata already makes as much clear in Dante’s very first chapter, ‘Childhood’: ”Defence and intimidation were both necessary operations in a city where quarrels between individual citizens and factions degenerated almost daily into violence and unrest […]. Spiralling hatred ended up dividing the largest family clans and even causing rifts in smaller ones. Coexistence in the city was precarious, marred by sudden outbursts of collective violence and individual coups de main, even during periods of relative calm when factions were attempting to work together.”

In response to and amid such upheaval, Santagata traces Dante’s attempts to establish himself in Florentine society, as a man of both letters and action. He also addresses the intriguing possibility that Dante translated an illness – believed by some to be epilepsy – into an intensely physical phenomenology of love in the Vita Nova.

Yet, perhaps most importantly, the author substantiates Dante Alighieri’s inexorable quest to forever readjust his own political standing.

His involvement with the aforementioned, pro-papacy Guelph faction being just one such example amid the many scattered throughout this more than comprehensive biography. A thoroughly well-researched biography at that, written from the premise of Dante being a father and courtier, as well as political partisan and philosopher.

Marco Santagata – who is a Professor of Italian Literature at the University of Pisa – has herein untangled many a complex web of family and political relationships for English readers; while in so doing, showing how the very composition of the Commedia was idiosyncratically influenced by local as well as regional politics.

But what one truly comes away with from having read this book of Two Parts (Florence and Exile), is Dante’s own (unwavering) high-octane belief in his own fate, wherein ”God had invested him with the prophetic mission of saving humanity.”

David Marx